The Neuroscience of Savant Syndrome: What We Know About Extraordinary Brain Skills

Some people can play a full concerto after hearing it once. Others can draw a cityscape in perfect perspective from memory, or tell you what day of the week any date in history falls on. These abilities are not the stuff of fiction – they are real-life examples of savant syndrome. In this article, we’ll explore what savant syndrome is, how it differs from other cognitive phenomena, and what neuroscience has uncovered about these remarkable cases. We’ll also look at what these rare abilities teach us about the brain’s potential and how cognitive training can support mental function in everyday life – even if we aren’t savants.

What Is Savant Syndrome?

Savant syndrome is a rare and fascinating phenomenon in which individuals display extraordinary abilities in specific cognitive domains – often in stark contrast to limitations in other areas. These abilities may include prodigious memory, lightning-fast calculation, musical talent, or artistic precision.

The term “savant” comes from the French word savant [savɑ̃], meaning “learned” or “scholar.” Historically, the condition was referred to as “idiot savant,” a term introduced by physician John Langdon Down in 1887 to describe individuals with severe intellectual disabilities who demonstrated striking islands of genius. However, due to the derogatory and inaccurate implications of the word “idiot,” the terminology evolved to “savant syndrome.”

While certain behaviors or traits associated with savant syndrome are mentioned in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), savant syndrome itself is not classified as a distinct diagnosis (in the section on autism spectrum disorder, DSM-5 notes that some individuals may exhibit “unusual interests or abilities”).

Who Can Have Savant Syndrome?

Savant syndrome can occur in individuals with neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or intellectual disability. It may also develop later in life due to brain injury, stroke, or central nervous system disease. Researchers distinguish between two types:

- Congenital savants, where abilities appear early in childhood, often alongside ASD (autism spectrum disorder);

- Acquired savants, who develop these abilities after neurological events like head trauma.

How Rare Is It?

Estimates suggest that approximately 1 in 10 individuals with autism may exhibit some form of savant abilities, though exact figures are hard to determine due to the variability in presentation and diagnostic practices (Treffert, 2009). Acquired savant syndrome – where these abilities emerge following brain injury or disease – is even rarer.

Common Types of Savant Skills

The abilities shown in savant syndrome are typically restricted to specific domains, such as:

- Music: Perfect pitch, the ability to play complex pieces by ear;

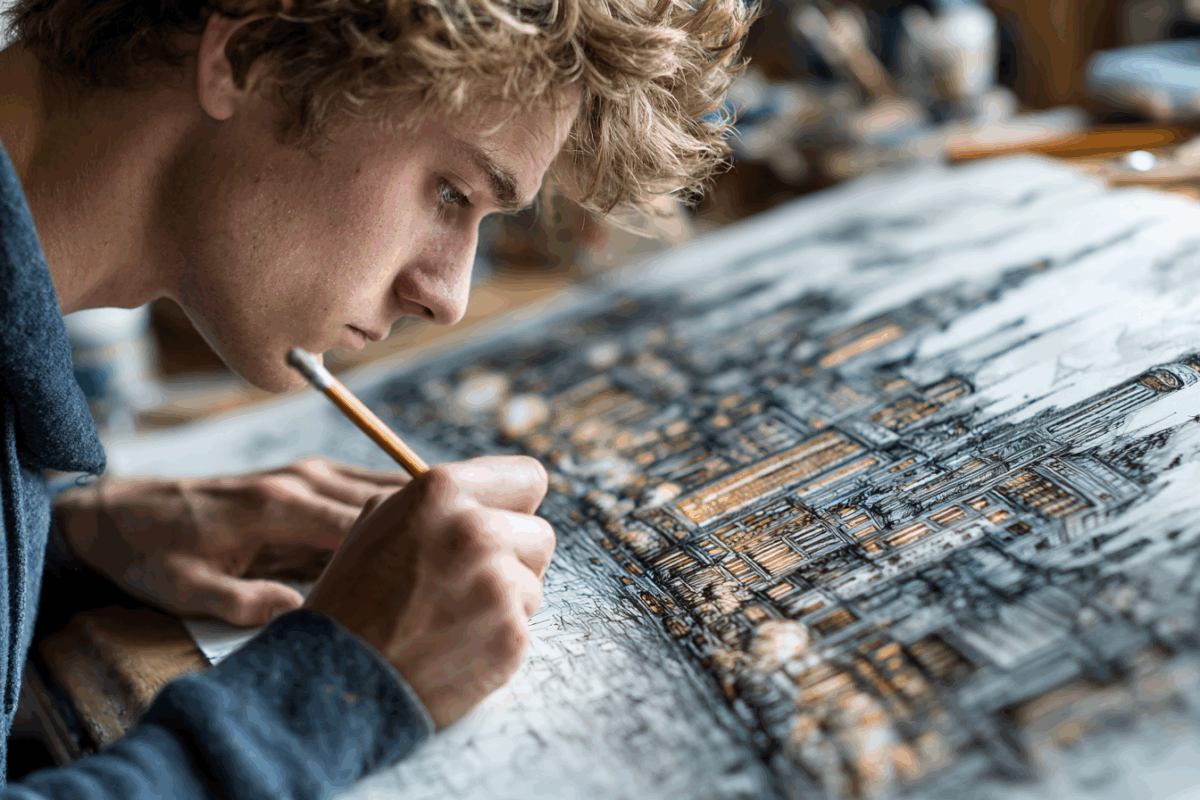

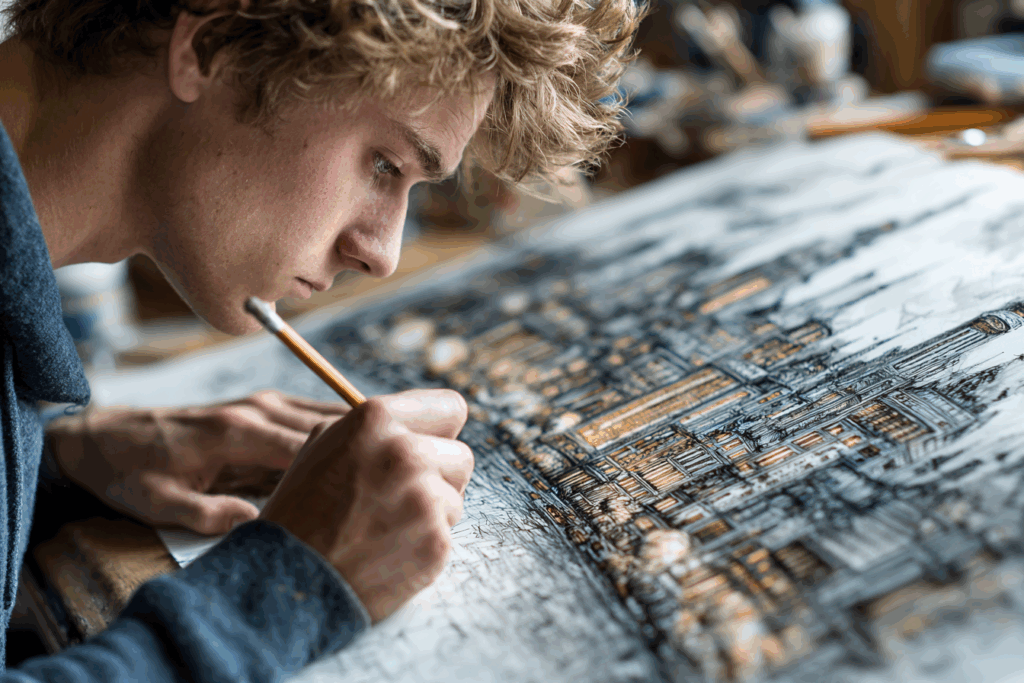

- Art: Hyper-realistic drawing or painting from memory;

- Mathematics: Lightning-fast calculations, calendar computations;

- Memory: Exceptional recall of facts, names, or historical dates;

- Spatial skills: The ability to mentally rotate objects or create 3D structures.

These skills are not usually learned in conventional ways. Instead, they often emerge spontaneously, sometimes even without formal instruction.

Real-Life Examples of Savants

One of the most well-known savants was Kim Peek, the inspiration for the character in the film Rain Man. Peek reportedly memorized over 12,000 books and could read two pages simultaneously – one with each eye.

Another striking case is Stephen Wiltshire, an artist who can draw intricate cityscapes from memory after a single helicopter ride.

Daniel Tammet, diagnosed with high-functioning autism, recited over 22,000 digits of pi from memory and learned Icelandic in a week. He also provides valuable self-reflections on how his brain processes information differently (Tammet, “Born on a Blue Day”).

What Neuroscience Tells Us About Savant Syndrome

While there is no single explanation for savant abilities, several hypotheses have been proposed:

- Compensatory brain plasticity: Damage or underdevelopment in certain brain areas may lead to enhanced activity in others. For example, individuals with left hemisphere deficits may show increased right-hemisphere specialization in visual or musical skills.

- Detail-focused cognitive style: Some researchers suggest that savants exhibit a local processing bias – an intense focus on detail rather than the whole (Happé & Frith, 2006).

- Increased working memory or perceptual capacity: In some cases, heightened memory storage or faster low-level perception may support these extraordinary skills (Snyder, 2009).

Neuroimaging studies have shown atypical patterns of brain activation in savants, but findings remain exploratory, and more research is needed to draw definitive conclusions.

Is It Just High Intelligence? Not Quite

Savant syndrome is not synonymous with high IQ. In fact, many individuals with savant abilities have below-average general intelligence or difficulties in other cognitive areas. What distinguishes them is the extreme specialization of a single or narrow set of skills.

This makes savant syndrome distinct from general “genius.” While genius may involve broad creative or intellectual capacities, savant abilities are usually limited in scope but extraordinary in execution.

Acquired Savant Syndrome: When the Brain Rewires Itself

Though most savants are born with their abilities, rare cases of acquired savant syndrome have been documented. For instance, after head trauma or neurological disease, some individuals have suddenly developed artistic, musical, or mathematical talents they never had before.

One case involved a man who, after a concussion, became obsessed with drawing geometric patterns and mathematical formulas – despite no prior interest in either. These cases raise important questions about latent potential in the brain and the mysterious ways in which neural networks adapt.

What Can We Learn from Savant Syndrome?

While savant abilities are rare, studying them offers insights into how the human brain stores, retrieves, and processes information. They reveal that:

- Cognitive abilities can be highly uneven but still extraordinary

- The brain has untapped reserves of perceptual and memory capacity

- Focused repetition and sensory input may activate specific circuits

Understanding savants helps neuroscientists explore the brain’s limits — and may inspire new approaches to learning, memory research, and even artificial intelligence.

Can Cognitive Training Unlock Hidden Abilities?

There is no scientific evidence that cognitive training can induce savant-like skills. These abilities appear to emerge from highly specific neurological conditions.

However, that doesn’t mean we can’t benefit from targeted mental practice. Cognitive training can help maintain or enhance functions like memory, attention, and processing speed – especially as we age or experience stress.

Online tools for brain training offer structured ways to engage with mental tasks in a motivating and measurable way. For those curious about their own cognitive profile, structured brain exercises can provide a useful window into areas of strength and improvement.

How to Support Cognitive Strengths in Everyday Life

Even without savant abilities, we can all take steps to optimize our cognitive potential:

- Practice pattern recognition through music, games, or languages.

- Challenge memory by learning sequences or stories.

- Train attention through mindfulness or focused tasks.

- Support brain health through sleep, exercise, and healthy routines.

- Engage with novelty to stimulate learning and neuroplasticity.

- Explore mathematical reasoning through number puzzles, online math games, or chess platforms, activities that engage attention, memory, and logical thinking.

These habits won’t turn us into savants, but they may help support underlying mechanisms – attention, memory, sensory processing, that are key to mental performance.

Conclusion: The Mind’s Untapped Potential

Savant syndrome is a rare and remarkable phenomenon. While it remains scientifically mysterious in many ways, it offers a glimpse into the astonishing diversity of human cognition.

By understanding how the brain can express such specialized abilities, we not only appreciate the power of neurodiversity but also learn more about how our own mental systems operate. And while we may never memorize a book at a glance or draw a city from memory, we can all benefit from deeper knowledge of how our brains learn, adapt, and surprise us.

The information in this article is provided for informational purposes only and is not medical advice. For medical advice, please consult your doctor.

References:

- Treffert, D. A. (2009). The savant syndrome: an extraordinary condition. A synopsis: past, present, future. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1522), 1351–1357. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2008.0326

- Tammet, D. (2006). Born on a Blue Day: Inside the Extraordinary Mind of an Autistic Savant: A Memoir. New York: Free Press.

- Happé, F., & Frith, U. (2006). The weak coherence account: Detail-focused cognitive style in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-005-0039-0

- Snyder, A., Bahramali, H., Hawker, T., & Mitchell, D. J. (2006). Savants, creativity and transcranial magnetic stimulation. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 13(9), 83–96.

- Snyder, A. (2009). Explaining and inducing savant skills: privileged access to lower level, less-processed information. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1522), 1399–1405. DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0290