Your Home and Your Brain: How Space Quietly Shapes the Way You Think

We tend to blame mental fatigue on overflowing inboxes, poor sleep, or a lack of discipline. We credit coffee for clarity and routines for focus. Yet cognitive science points to a quieter, more constant influence on how we think, decide, and regulate ourselves: the space we live in.

Your Home as a Cognitive Ecosystem

Your home is not just a place where life happens. From the brain’s perspective, it is a cognitive ecosystem – a continuous stream of data that your nervous system must interpret, moment after moment.

Every shadow, texture, sound reflection, and spatial transition is a small demand on the brain’s attention and regulatory systems. Most of these demands remain invisible to consciousness, yet together they shape attention, emotional tone, and mental stamina.

When the environment aligns with our biological expectations, this interpretation happens efficiently and quietly. When it does not, the brain pays what can be described as a “cognitive tax.” This tax rarely feels dramatic. Instead, it accumulates slowly, showing up as restlessness, brain fog, irritability, or the sense that rest never fully restores you.

To live and think better, we need to understand the invisible dialogue between our neural systems and the spaces we inhabit.

The Hidden Mechanics of Cognitive Load

The human brain never truly switches off. Even in moments of deep relaxation, the nervous system continues scanning the environment for signals of safety, coherence, and usefulness. This is not anxiety – it is baseline neurobiology.

Modern homes often fall into one of two high-load categories.

Some environments create excessive cognitive load. Visual clutter, unfinished projects, competing colors, and constant background noise force the brain to engage inhibitory control – the mental energy required to suppress irrelevant stimuli. Over time, this becomes exhausting. This often looks like open shelves packed with mismatched objects, work materials bleeding into living areas, multiple screens competing for attention, or spaces where nothing ever feels visually “finished.”

Other spaces do the opposite. They are overly sterile, flat, and monochromatic. These environments push the brain into search mode, where attention wanders restlessly, scanning for information that isn’t there. Typical examples include ultra-minimal interiors with smooth white walls, uniform lighting, glossy surfaces, and almost no texture, depth, or visual variation to anchor the eye.

The problem in both cases is not style. It is legibility. A brain-friendly home is one that is easy for the nervous system to read.

Why “Perfect” Spaces Can Feel Mentally Uncomfortable

Minimalist interiors are often associated with calm and order. And when applied thoughtfully, they can indeed support clarity. The paradox appears when minimalism strips away too many sensory cues.

Smooth surfaces, uniform lighting, strict neutrality, and visual emptiness may look serene, but they offer very little information for the perceptual systems. Such spaces can begin to feel impersonal, almost clinical – orderly and controlled, yet emotionally distant. There is little texture to touch, little depth for the eye to explore, and few signals that say, “this space is lived in, inhabited, and safe to relax in.”

People rarely describe this as dissatisfaction. Instead, they say things like:

- “I can’t fully relax here.”

- “I keep checking my phone.”

- “It’s beautiful, but something feels off.”

From a cognitive perspective, the environment is incomplete – and the brain is quietly compensating for what the space no longer provides.

Understimulated Does Not Mean Rested

A common myth is that reducing stimulation automatically leads to rest. Cognitive science suggests otherwise.

The nervous system functions best within an optimal range of stimulation. When stimulation drops too low for extended periods, the brain does not settle. It compensates by increasing internal activity. Attention drifts. The mind seeks novelty. Small rewards become more tempting. This is not a failure of discipline; it is regulation. In a sensory-poor home, the brain often remains in low-grade search mode, preventing full cognitive recovery even during downtime.

Thinking Is Embodied: Why Touch Shapes the Mind

Cognition is not confined to the head. It is embodied, shaped continuously by signals from the body.

Touch plays a central role in this process. The somatosensory system processes texture, temperature, resistance, and weight, and these signals directly influence emotional regulation and cognitive flexibility.

Perfectly smooth, synthetic surfaces provide almost no tactile feedback. Over time, this can leave the nervous system feeling unanchored.

In contrast, natural materials, untreated wood, linen, wool, stone, ceramics, provide subtle variability and resistance. This tactile richness acts as a sensory anchor, signaling stability and physical reality.

A home optimized only for visual cleanliness may inadvertently deprive the body of inputs that help stabilize the mind.

Visual Hunger: Why Flat Spaces Fatigue the Brain

The visual system is one of the brain’s most energy-intensive systems. It evolved to process environments filled with depth, shadow, irregularity, and layered complexity. Many contemporary interiors rely on flat planes, right angles, and uniform lighting. While visually orderly, these spaces offer little for the eye to read. Attention slips into scanning mode, searching for stimulation elsewhere.

Natural environments work differently. They are rich in fractal patterns – organized complexity that repeats at multiple scales. When the eye encounters these patterns, it enters a state often described as soft fascination. Attention is gently engaged, allowing higher cognitive systems to recover. This explains a simple observation: people can watch fire, waves, or leaves moving in the wind for long periods without boredom, yet feel uneasy in visually empty rooms. The difference is not entertainment – it is neural compatibility.

Sound, Echo, and the Feeling of Safety

Sound reaches the brain’s emotional processing systems faster than sight. Long before we consciously interpret a space, our nervous system is already listening, using sound to assess whether an environment feels open, exposed, or sheltered.

Rooms filled with hard, reflective surfaces often resemble open or unfinished spaces. Voices bounce, footsteps echo, and even small sounds linger in the air. This acoustic sharpness keeps the nervous system in a state of subtle alertness – not loud enough to feel stressful, but persistent enough to prevent full relaxation.

Spaces that absorb sound tell a different story. Soft textiles, uneven surfaces, books, rugs, and layered furnishings gently catch and soften noise. Sounds fade more quickly, boundaries feel clearer, and the space reads as enclosed and protective. The nervous system settles, not because the room is silent, but because it feels held.

This is why some homes can feel tense even when they are quiet, while others feel calm and welcoming despite soft background sounds like conversation, music, or everyday movement.

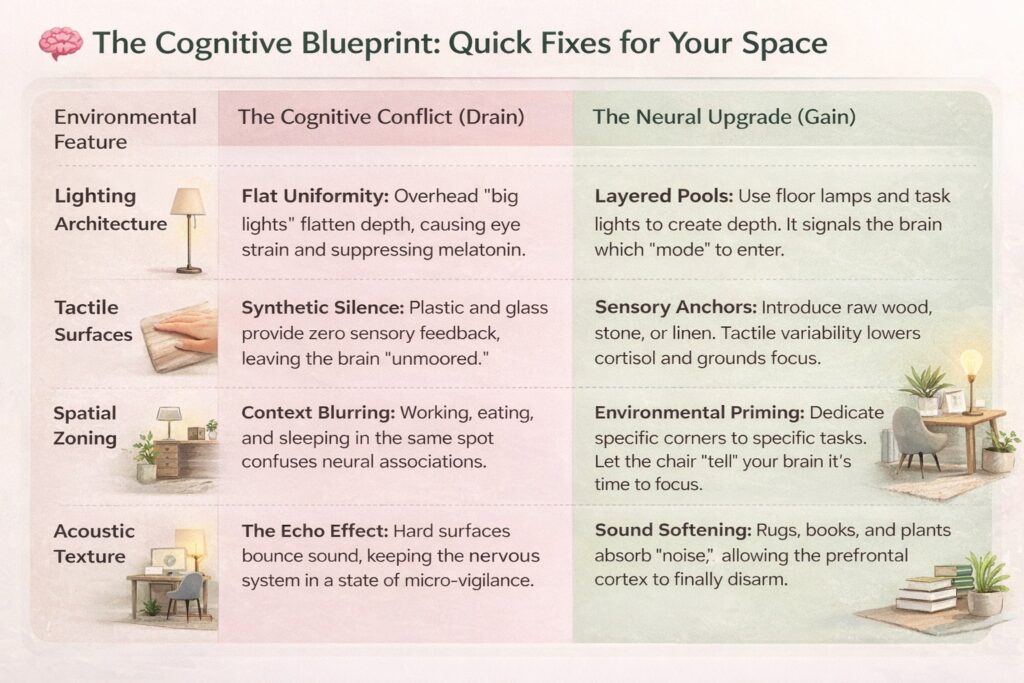

Practical Insights: How to Build a Brain-Supportive Home

This is not about changing your style or renovating your life. It is about improving the quality of information your environment provides.

Below are seven cognitively meaningful principles.

1. Design for Sensory Balance, Not Extremes

The brain struggles both with overload and with deprivation. Spaces that are visually chaotic demand constant filtering. Spaces that are overly empty or sterile force the brain into search mode. In both cases, the nervous system works harder than it needs to.

Practical takeaway: If a room feels overwhelming, remove competing visual elements from your direct line of sight (for example, open shelves or mixed materials in one area). If a room feels empty or cold, add one or two grounding elements – a textured rug, a fabric throw, or a piece with visible structure – to give the brain something to anchor to.

2. Focus on High-Exposure Zones

The nervous system responds most strongly to repetition. The areas you use every day shape your cognitive state far more than rooms you rarely enter.

Practical takeaway: Start with the place where you sit the longest (sofa, desk, bed). Improve that zone first by adjusting light, texture, or sound before changing anything else in the home.

3. Feed the Sense of Touch Intentionally

Touch is not decoration; it is regulation. The materials your body contacts daily send constant signals to the nervous system.

Practical takeaway: Notice what your hands and feet touch most often. Replace at least one smooth, artificial surface with a tactile one – a woven cushion, a wooden surface, a textile rug – in areas where you rest or work.

4. Replace Flat Lighting with Layers

Uniform overhead lighting flattens space and strains the visual system. Without contrast, the eye works harder to interpret depth.

Practical takeaway: Instead of relying on one ceiling light, add a secondary light source at eye or waist level, such as a table or floor lamp. Use it in the evening to create a softer visual field around where you sit.

5. Give the Eye Something to Read — Not Everything to Look At

The brain prefers organized complexity. Too many visual points compete for attention; too few leave the eye searching.

Practical takeaway: Choose one visually interesting element in a room – a patterned rug, textured artwork, or natural material – and let it be the focal point. Remove or quiet competing items nearby.

6. Soften the Acoustic Environment

Harsh acoustics keep the nervous system alert. Sharp echoes and sound reflections subtly signal exposure.

Practical takeaway: If voices echo or footsteps sound sharp, add soft surfaces near where you spend time: curtains, upholstered furniture, cushions, or a rug. You don’t need silence – you need sound to fade more quickly.

7. Add Signals of Life, Not Just Objects

Living elements matter because they change. The brain reads growth and subtle movement as signs of a habitable environment.

Practical takeaway: Instead of placing one plant as decoration, group two or three together in a space you use daily, such as near the sofa or workspace. The brain reads this as a small living system, not a visual accent.

Environment and Mental Training: A Necessary Partnership

A well-designed environment does not make you smarter, but it makes thinking easier. When your space reduces background cognitive noise, your brain spends less energy filtering distractions and more energy doing the work you actually care about.

Mental practices that train attention, memory, or cognitive flexibility are far more effective when they take place in a supportive setting. Trying to focus in a space that constantly pulls your attention elsewhere is like exercising on unstable ground – possible, but unnecessarily exhausting.

When your environment aligns with how the brain naturally works, mental effort feels lighter. Focus becomes more consistent, routines are easier to maintain, and the skills you practice are more likely to carry over into everyday thinking, decision-making, and problem-solving.

The Takeaway: Designing for the Internal View

We spend around 90% of our lives indoors. If our homes are designed only for the eyes of others, we neglect the most important occupant: our own nervous system. A space that speaks the brain’s language – through depth, texture, acoustic warmth, and living signals — does not just look better. It functions better.

By treating your home as a cognitive ecosystem rather than a visual object, you reduce the hidden tax on attention and regulation. The result is not perfect calm, but something more realistic and more valuable: a mind that spends less energy compensating – and more energy thinking, connecting, and living. Your environment is always shaping how you think. The question is whether it is quietly helping – or quietly asking too much.

The information in this article is provided for informational purposes only and is not medical advice. For medical advice, please consult your doctor.