Knowledge Vs Intelligence – Uncovering the Cultural Link

When it comes to knowledge vs intelligence, our society seems to put greater value on the latter. But is it really an accurate measure of someone’s mind? What about useful, general understanding of the world or deep cultural learning?

In this article, we will explore what IQ tests are, where they came from, and what scientists are now doing to make sure that any kind of intelligence test stays unbias but also culturally relevant.

STARTING WITH INTELLIGENCE

Intelligence is an important part of how our society values individuals.

For example, intelligence (or the appearance of it) is often a key criterion for schools when they admit students. For the most part, colleges and universities rely on it to give scholarships, grants, and awards. Even employers look for signs of intelligence when selecting the best candidate for a job.

Because this is so important in our daily lives, it also means it’s vital to understand how we measure it. But not only that, we need to know how we can improve these measurements.

USING IQ AS A MEASURMENT

One of the most basic ways we measure intelligence is by testing an individual’s IQ (intelligence quotient.)

Most people think this is how we measure how smart someone is. However, the series of tests only give a final “metal age” through different critical thinking and reasoning scenarios. This number is then divided by their actual age (which is sometimes called “chronological age.”) But what’s more important, is IQ exams also provide a simple way to compare multiple individuals of varying ages and mental abilities.

And while for many practical applications the IQ system provides, it’s not without its flaws.

Our understanding of intelligence has evolved

The more we learn about the human brain and cognitive abilities, the more we understand one key fact… There are, in fact, MANY types of intelligence. And these types of know-how can be affected by things such as culture, education background, and even environment.

“IQ scores are great at testing a specific type of intelligence in a specific type of person in a specific type of culture”

If we focus on the quote above, we start to see one of the biggest problems with IQ tests. The same issue also seeps into other areas of psychology and cognitive science. Basically, it’s mostly Western, educated, white men that develop, implement, and review the science and research that underpin the IQ scoring system.

So, what happens when we try to test the intelligence of people who may not have had the same background?

Anyone who didn’t get an education in a “western” school would end up with a very different score. Not to mention if their life experiences are very different from the “focus group” (no matter which country you come from), the results wouldn’t help anyone measure how smart that person is. And this isn’t even close to understanding that person as a whole.

EXPLORING THE LINK BETWEEN KNOWLEDGE VS INTELLIGENCE

If someone had to name all 50 states in America, the results would probably be skewed. It would show that Americans were smarter than the rest of the world. If the test, however, asked how to calculate the score of a Cricket match, those very same Americans might be labeled as ‘underperformers.’

Granted, these are light-hearted examples. However, it’s easy to see how the IQ test falls short. The general knowledge an individual has because of their location, culture, and past experience will definitely affect their scores. Sow, how can we create measures of intelligence which as unbiased, culturally-neutral, and universally relevant?

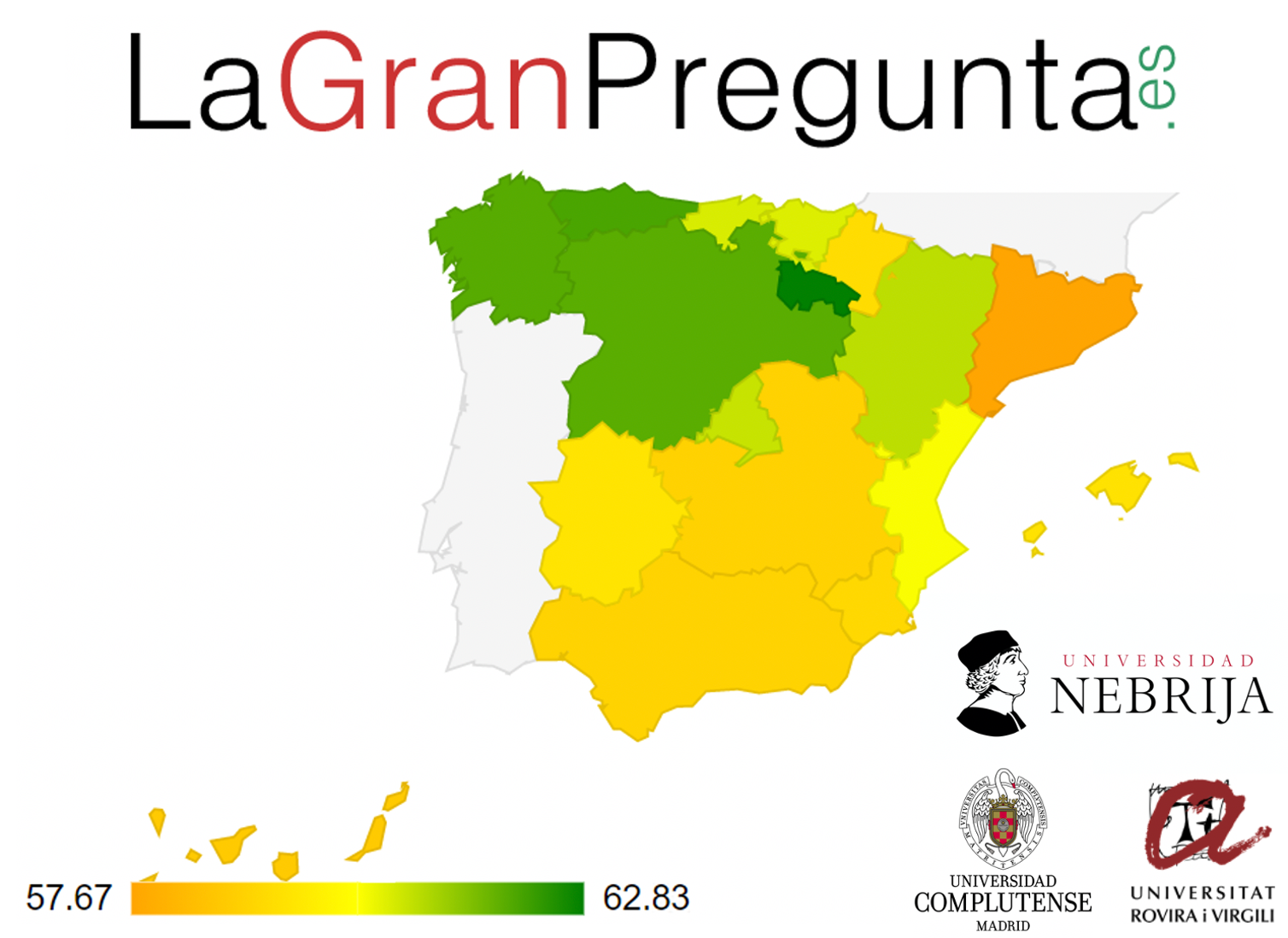

It was with this hurdle in mind that scientists in Spain have developed a research project known as ‘The Big Question’ (in Spanish, ‘La Gran Pregunta’). It investigates the role that ‘general cultural knowledge’ has on intelligence scores, and how location affects the population’s average scores in cultural knowledge.

WHAT EXACTLY IS THE BIG QUESTION?

Jon Andoni Duñabeitia (director of the Cognitive Science Center (Centro de Ciencias Cognitivas, or C3, in Spanish) of Nebrija University) created the research project The Big Question.

But he wasn’t alone. Teams of researchers from the Complutense University of Madrid and the “Rovira i Virgili University” designed the study to measure variations in the cultural knowledge of the people living in the various Autonomous Communities in Spain.

Thanks to the data collected in the project, the research teams will be able to draw a scientifically sound map of shared knowledge that will serve as a baseline of general culture knowledge in Spain.

How is it organized?

The project is a quiz that gives general knowledge questions about different general knowledge categories. There are 37 different categories that address thematic areas such as zoology, astronomy, inventions, discoveries, architecture, mythology, folklore, etc.

The research platform has a list of 1,300 questions. After a player completes a short questionnaire on basic sociodemographic data, they get 60 randomly selected questions. So, each time they enter to play a game, they will get a different combination.

In the first two weeks that the platform was live, players from all over the autonomous communities finished more than 36,000 games. At the moment, the average score on the test (at the national level) is 60%, with some differences between communities.

Once the “data cleansing procedure” has been applied, the provisional data shows an unequal distribution between territories. However, these differences never exceed 5%. And, the average of correct answers per Autonomous Community ranges from 57% to 62%.

Above the average we find:

- Galicia

- Castile and León

- Principality of Asturias

- La Rioja

- Aragon

- Community of Madrid

- Basque Country

- Cantabria

- Valencian Community

Scoring below the average was:

- Region of Murcia

- Balearic Islands

- Autonomous Community of Navarre

- Andalusia

- Castilla-La Mancha

- Canary Islands

- Catalonia

- Extremadura

QUIZ SCIENCE & QUESTIONS

The history of databases on general culture is still quite recent and far more scarce than some might think. In fact, it was only in the early 80s that Nelson and Narens found that there was no database for general culture facts. There was also no measurement to see whether there was data more difficult to remember than others.

So, they compiled a list of 300 questions from books, atlases, colleagues, friends, and other sources of information they thought relevant. Next, students from two U.S. universities answered these questions and collected different cognitive and metacognitive measures.

Over the following decades, these questions were used in countless research in cognitive science projects.

However, the passage of time changed this compendium of facts and data – it just wasn’t 100% relevant anymore. Society advances and changes, and with it cultural knowledge relevant to each historical context. This led a group of scientists in 2013 to review the original set of questions and see how it had evolved over the past three decades.

Nearly 700 students from different universities took the slightly revised test, and the results were very interesting.

There were some differences in the general knowledge answers in both experiments (for example, in 1980 only 7% of the sample knew the capital of Iraq, and in 2013 this value increased to 47%). However, the authors concluded that the set was still valid.

But things didn’t end there…

Recently, a team of Spanish scientists decided to test the knowledge of almost 300 participants from two universities. This was so they could explore whether the results of the North American tests could be generalized to Spain. When they analyzed the consistency in the answers to the same questions (by students from different countries), they found a very high correlation between the two groups. This indicated high intercultural stability.

However, the researchers also found different aspects of knowledge between Americans and Spaniards. For example, 97% of the Spanish sample knew that Venice is the Italian city best known for its canals. However, only 46% of the North American sample answered correctly.

All these studies, and similar ones in various countries, have involved a very limited number of questions. Also, they have generally focused on the university population of young adults. Obviously, this can hardly be representative of our entire society.

But now, thanks to new technologies and the use of the Internet, ‘The Big Question’ allows scientists to create the most current and complete database on data and facts of general culture. This means they can create a “Trivial Pursuit style” of national dimensions and with a scientific foundation.

GENERAL KNOWLEDGE VS INTELLIGENCE RESULTS

There is no scientific agreement on whether general knowledge is part of a type of intelligence, or whether it is an indicator or a measure of it.

Some intelligence tests have sections of general knowledge. And, many authors claim that this data would be equivalent or belong to crystallized intelligence – which is are the facts, data, and experiences acquired and memorized over the years.

Others argue that there is a greater connection with reasoning and working memory. These aspects are more related to fluid intelligence – which refers to the mental ability to apply reasoning and logic to various new situations that will help us acquire new knowledge.

That being said, some authors suggest that the results of a general knowledge test ( that is properly updated, relevant to the participants, and properly psychometrized) can still be considered a fairly reasonable representative value of intelligence.

FINAL THOUGHTS

It’s not just IQ that’s important. General knowledge is very relevant and informative – especially for the future of work and society. In a changing world with a strong global and intercultural character, advances will come hand in hand with projects that promote knowledge, culture, and scientific collaboration. This is why The Big Question (and other tests like it) is so important.