Healthy Diet Experiment – Training People’s Brains To Eat Better

When it comes to food, many of us might feel like we’re spoiled for choice. A single product will have countless variations to entice customers – often advertising that they’re part of a healthy diet. However, what we don’t realize is that we’re walking through a nutritional minefield.

And it’s this minefield that causes so many weight issues. Here’s where an interesting pilot study published in the journal Nutrition & Diabetes comes into play.

THE FIRST PROBLEM

Some people think that sticking to a healthy diet is a simple thing – that all it takes is a little willpower. They also claim anyone who’s overweight or obese is “just being lazy.”

But the thing is, that’s just not true.

Firstly, our primitive minds are hardwired to seek out stuff that’s high in calories or whatever is harder to find in nature. That’s why we crave salts and fats – it gave our ancestors the energy to hunt and just stay alive.

THE SECOND PROBLEM

As if that’s not hard enough to fight against in the first place, we now live in a food environment that’s chock-full of things that are just fancy variations on fat, sugar, and salt. For many people, it can form a very real addiction – and this isn’t even including things like stress-eating.

If we boil it down, the food industry created an addiction so they could sell more products.

“We don’t start out in life loving french fries and hating, for example, whole-wheat pasta,” senior author Susan Roberts, director of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Energy Metabolism Laboratory, said in a statement. “This conditioning happens over time in response to eating – repeatedly – what is out there in the toxic food environment.”

Scientists know that once people are addicted to unhealthy foods, it is usually very hard to change their eating habits and get them to lose weight. They also know that high-calorie foods will activate the pleasure centers of the brain.

We crave the rush of dopamine, so we eat foods that give it to us.

THE HEALTHY DIET STUDY

The pilot study that took place in 2014 was one of the first that took a look at this connection through modern medical equipment. They wanted to see if there was indeed a neurological link – and even if it could be trained out of the brain.

The small pilot started with 13 obese men and women that fell within certain testing conditions…

- Between 21 and 65 years old

- Generally healthy

- Have a certain high body mass index

- No previous signs of claustrophobia

- Employed by one of four worksites that housed the test

- A doctor’s note supporting their participation in the test

After selection, part of the group would start with the program right away. The other group (the control group) would have to wait 6 months before receiving their “weight control intervention.”

So, what was the test?

The intervention group would use an adaptation of the “I” Diet by SB Roberts and BK Sargent. This particular plan puts a focus on portion control and low-glycemic foods. Protein and fiber targets were also pushed to the higher end of the recommended scales – with the idea that these “slow” burn foods would help people from being hungry during the day.

But this sounds like just a diet, right? Where’s the brain intervention part?

Well, the healthy diet wasn’t the only thing the intervention group got. They also received…

- 19 support meetings over 24 weeks

- Individualized emails from specialized nutritionists

- Specific menus for an energy reduction goal of 500–1000k cal per day

- Healthy recipe ideas

- A suggested timetable of evenly spaced-out meals

- A list of “free” foods to curb hunger cravings

In essence, they were given a lot of positive support to help them stay on their healthy meal plans. The control group, however, would eventually get the meal plan but would have to be waitlisted for six months.

THE SCIENCE PART

Both groups went through the same tests.

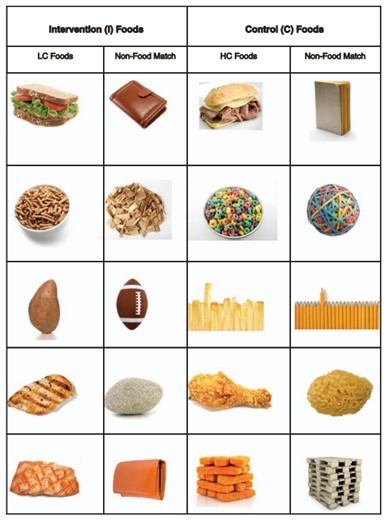

All participants also got a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scan before and after the six months were up. While in the machine, they were shown 40 food and 40 non-food control-image cues.

The food cues included both high- and low-calorie options. The non-food cues were images that looked similar to the food cues but were quite not food (e.g. a wallet or pencils).

The researchers focused their scans on each participant’s striatum.

This is the area that’s often associated with the brain’s dopamine-rich reward processes. So, if the support system had created any changes in the way the test subjects viewed food, it would be there.

What was the result?

They found significantly higher average amounts of activation in this area for the low-calorie food images than high-calorie foods, but only in participants who had already been through the I Diet program. The control participants showed the opposite: more activation in the striatum for high-calorie foods.

This suggests that changing what we eat eventually changes what we crave.

FINAL NOTES

However, there are a few things to keep in mind. First, the study was done in 2014 – and there have been other studies since then that have probably built on this concept. Also, technology had continued to improve so further results might have found deeper data.

“There is much more research to be done here, involving many more participants, long-term follow-up and investigating more areas of the brain,” Prof Roberts said. “But we are very encouraged that the weight-loss program appears to change what foods are tempting to people.”

Secondly, this is by no means a personal guide – simply a scientific insight on the power of the brain (for both negative and positive). The world continues to be a minefield of unhealthy choices and not everyone can get the support necessary to “change their brains.”

Also, things like gastric bypass surgery aren’t sure fixes for any weight problems.

This is because there is a percentage of people that will still gain the weight back afterward. The Boston researchers point out another important fact – that these kinds of “fixes” take away the enjoyment of food instead of making healthier food something we would crave.

Still, the results are promising.